In honor of Black History Month we looked into the archives to share these incredible stories with you. Learn about soldiers on bikes, female cyclists’ cross -country adventures, and one of the world record holders who set the record for the fastest bicycle mile!

Katherine T. “Kittie” Knox

Kittie Knox, courtesy USA Cycling

In 1890, when the “bicycle boom” hit full steam, many cycling clubs rapidly sprung up all over Boston, where cycling was most popular. These cycling clubs would travel to nearby towns for riding competitions, social fun, politicking, and advocacy. A trailblazing pioneer that would go down in HERstory is Miss Katherine Towle Knox. Katherine, more commonly referred to as Kittie, was born on October 7, 1874, in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. When Kittie was just around seven years old, her father passed away from an unknown cause. In the wake of her father’s death, Kittie, her mother, and her older brother Ernest moved to the West End of Boston where she began to show interest in cycling. – USA Cycling

Kittie Knox was a true cycling pioneer. Her story of courage in the face of racial tension helped desegregate the world of cycling and offered a hopeful vision for a future that. – USA Cycling

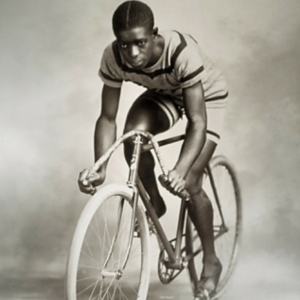

Major Taylor

Science History Images/Alamy

Bikes, Race, and Racing in 1928

Photo: Baltimore Afro-American newspaper, 1928. Addison Scurlock, photographer. Photograph courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

In 1928, five Black women set off from New York City on a 250 mile adventure to Washington D.C. Their three day ride was about personal pleasure and challenge and calls into question our ideas of who bicycled in history and why.

Historian Marya McQuirter has a deep insight into the 1928 ride.

America’s Black Army on Wheels – The 25th Infantry Fort Missoula Buffalo Soldiers.

In 1896, the US military gathered a small group of soldiers to test a new military mode of transportation — the bicycle.

With a claim that “unlike a horse, a bike did not need to be fed and watered and rested, and would be less likely to collapse,” — they clearly never met my bike — the army selected a regiment to test the utility of the bicycle in service. Their choice for the job? The 25th Infantry Fort Missoula Buffalo Soldiers.

The Buffalo Soldiers were African American soldiers who fought in segregated units after the Civil War. The newly formed bicycle unit consisted of eight enlisted men and their white commander, Lieutenant James A. Moss. The 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps at Fort Missoula, Mont. — or “Iron Riders” as they were known — rode 1,900 miles to St. Louis on brand new Spalding single gear bicycles, attracting great attention where ever they stopped and even their own riding press detail. After the test trip, Lt. Moss noted that, while the bike mounted soldiers may not replace the mounted cavalry, the bicycle corps would best serve as adjuncts to both cavalry and infantry.

More info and watch here.

Courtney Williams

Black people were systematically excluded from cycling for a long time, as with other sports in U.S. history, and ended up doing it less as a result. That seems to be rapidly changing. According to a 2013 report by the League of American Bicyclists and the Sierra Club, from 2001 to 2009 ridership among Black cyclists doubled, despite the lack of representation in advocacy groups and the lack of cycling infrastructure in communities known as “transit deserts.” A number of minority cycling groups have sprung up in recent years all over the country, including Red, Bike & Green, a collective founded in 2007 and aimed at creating a black bike culture; and the National Brotherhood of Cyclists, founded the following year by a network of affiliated black cycling clubs. In 2011, a group called Black Women Bike: DC was formed and two years later the national Black Girls Do Bike was born on Facebook. Read more about Courtney’s story.

Black Girls Do Bike: Newport

Shero Allyson McCalla, Bike Newport’s Director of Operations and certified Bicycle Instructor, launched the Newport chapter of Black Girls do Bike in October 2020. “Our chapter of Black Girls Do Bike brings together women of color to share a passion, ride together, motivate one another, and grow the community of Black girls who do bike.” So far, the Newport Chapter has nearly 200 people in its Facebook group – which is private, but open to any WOC or supporter who seeks a bicycling community. Read more about the Black Girls Do Bike Newport Chapter.

Community Awareness & Action

Recently, bicycling organizations around the country have announced action plans to fight racial injustice within the cycling community. The organization PeopleforBikes focuses on three main objectives in their action plan: educate people — staff, industry, advocacy and community, operationalize equity and amplify voices. They write, “fighting racial injustice connects to the very core of PeopleForBikes’ mission — to make biking better for everyone. The development of equitable access for all to safe bike networks that connect to jobs, education and other essential services can enhance opportunities, increase social and mobility justice and build better communities. Breaking down the barriers that prevent BIPOC from riding is a bigger challenge than just building safe places to ride.” Read more about their next steps to fight injustice.

Tamika L. Butler wrote a story in Bicycling Magazine “Why we must talk about RACE when we talk about BIKES” that speaks about the intersection of race, equity, social justice, and bicycling and shares the stories of 14 Black riders. Butler, who was the executive director of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition and now runs a social justice consulting business, writes “to truly make transformational change for all people who bike, we must go beyond a “Bike Month” or an occasional unity ride. We also must get beyond the narrative that only people who (too often self-righteously) make a lifestyle decision to bike are worthy of our targeted marketing campaigns, advocacy, and celebration. We must get past a strategy that assumes cisgender white maleness as the norm. We must get past an ethos of exclusion. Once we can get past these things as a bicycle community, we can finally celebrate what bicycling should truly be about—the power to be free and move freely.” Butler notes, “bicycling cannot solve systemic racism in the United States. But systemic racism can’t be fixed without tackling it within cycling.” Butler emphasizes that people and organizations must back their statements with anti-racist action to see real change. Read more about Butler’s story and the stories of other black riders.

A Peak into the Black Cycling Community Today

There are many riders, competitors, mechanics and advocates who are making Black history in cycling, a sport where Black people typically get little exposure.

Instagram @lalitasotera

Laura Solís is a freelance mechanic and a recipient of the 2017 Women’s Bicycle Mechanic Scholarship from QBP. She hosts an instructional YouTube channel where she shares her knowledge with the world! Bicycling Magazine wrote an article shining light on just a few of the many Black individuals who are making waves in the world of cycling, including Laura Solís! Read the full article.

Photo: Kadeena Cox

Kadeena Cox is a sprinter, time-trial cycling champion and Paralympian who has won several world and Olympic titles. She has brought home gold, silver, and bronze medals from the Rio Paralympic Games along with medals from various World Championships. She notes that the cycling world is “dominated by white, middle-class people” and pushes for representation of sports stars from diverse backgrounds.

Photo: Leo Rodgers – Critical Mass Ride – Ybor City, FL

Leo Rodgers is an irrepressible cycling hero and amputee. He is a Paralympic champion and has competed at famous gravel events including Dirty Kanza and Grinduro. He never shies away from a challenge, despite all that he has endured. Read more about Leo Rodger’s story from Bicycling Magazine.

Bike Newport

Bike Newport